The Drone Revolution: How Cheap Tech and DIY Tactics Redefined the War in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine has become the most significant real-world laboratory for modern military technology, and no single system has proven more transformative than the uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone. While advanced military hardware has played a crucial role, the conflict’s most profound surprise has been the ascendancy of cheap, commercially available drones. These systems, often costing less than a used car, have been adapted with battlefield ingenuity to perform tasks once reserved for multi-million-dollar aircraft, fundamentally altering tactical dynamics and challenging long-held military doctrines.

This analysis explores the remarkable evolution of drone warfare in Ukraine. It examines Russia’s pre-war doctrinal plans for a sophisticated, integrated “reconnaissance-strike complex” and contrasts them with the attritional reality of the battlefield. We will detail the operational shortfalls that created a vacuum for commercial and foreign-made drones to fill, the bottom-up tactical revolution they inspired, and the profound implications of this new era of warfare for global security. The conflict has demonstrated that in modern warfare, battlefield dominance is not just about possessing the most advanced technology, but also about the ability to adapt and innovate at speed. As Air Marshal Johnny Stringer, deputy commander of NATO’s Allied Air Command, observed, the new reality is that:

“you could conduct most if not all of the airpower roles for the price of a drone, a laptop, and some imagination.”

Our examination begins with a look at the highly structured, top-down drone strategy Russia brought into the war.

2.0 Russia’s Grand Plan: The “Reconnaissance-Strike Complex”

Prior to its 2022 invasion, Russia’s military doctrine for uncrewed systems was centered on a sophisticated concept known as “reconnaissance-strike” and “reconnaissance-fire” complexes. This doctrine was designed to be the cornerstone of Russian targeting, creating a seamless, high-speed link between real-time intelligence gathered by UAVs and rapid strikes from artillery or missile systems. The ultimate goal was to achieve battlefield information dominance, allowing Russian forces to identify and destroy high-value targets faster than an adversary could react.

This concept was not merely theoretical. Russia had actively applied and refined it during its intervention in Syria and in numerous military exercises. The doctrine envisioned the integration of its workhorse Orlan-10 reconnaissance drones with powerful long-range strike assets, such as the Iskander-M and Tochka-U missile systems. Before the war, the Russian Ministry of Defence (MOD) confidently claimed to possess one of the world’s largest operational drone fleets, with an estimated 2,000 UAVs integrated across its Aerospace Forces, ground forces, and naval fleets.

However, Russia’s doctrine failed to account for the realities of a high-intensity conflict, and a significant gap between its grand plan and its initial application in Ukraine emerged. The Kremlin’s belief in a swift victory meant that there was little planning for the significant quantities of drones a protracted war would demand. Furthermore, the “reconnaissance-strike complex” proved sluggish in practice. The response time between detecting a target and engaging it was often too slow to effectively strike mobile Ukrainian units, undermining the core principle of the doctrine. This doctrinal failure stemmed from a key organizational difference: Russian drones operated at the battalion level or below, whereas Ukrainian forces broadcast drone data to higher echelons, enabling a much faster artillery response. This disconnect between Russia’s strategic ambitions and its operational realities on the ground set the stage for a dramatic and unforeseen shift in drone warfare.

3.0 The Reality of Attrition: Military Drones and Industrial Shortfalls

Despite entering the conflict with a large on-paper drone fleet, the high-intensity nature of the war in Ukraine quickly exposed critical weaknesses in Russia’s military UAV platforms and its defense-industrial base. The demands of a full-scale war revealed that Russia’s drones were often technologically lacking and that its industry was unprepared to produce them at the scale and quality required, forcing a difficult confrontation with deep-seated industrial shortfalls.

Key Russian-Made Military UAVs Deployed in Ukraine

| Name | Primary Function | Reported Range (km) |

| Eleron-3 | ISR | 30 |

| Orlan-10 | ISR and combat | 120 |

| Orlan-30 | ISR | 300 |

| Korsar | ISR and combat | 250 |

| Takhion | ISR | 40 |

| Forpost | ISR and combat | 250 |

| Orion | ISR and combat | 250 |

| KUB | Loitering munition | 40 |

| Lancet variants | Loitering munition | 40 |

Performance and Limitations

Russia’s primary military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) drone, the Orlan-10, became a ubiquitous asset for artillery spotting. Its more advanced counterpart, the Orlan-30, played a more specialized and critical role due to its ability to carry a laser designator. This allowed it to “paint” targets for precision-guided munitions like the 152-mm Krasnopol artillery shell, significantly improving the accuracy of Russian fires when available.

However, Russia’s fleet of dedicated combat drones, such as the Forpost-R and Orion, had a limited impact. These medium-altitude, long-endurance (MALE) drones proved highly vulnerable to Ukraine’s increasingly effective air defenses. After suffering initial losses, their use was largely confined to ISR missions far from the front lines, failing to provide the rapid “sensor-to-shooter” capability needed to destroy mobile targets.

Loitering munitions, or “kamikaze” drones, proved more effective. The KUB and Lancet variants were frequently used in tandem with reconnaissance UAVs, which would locate targets like Ukrainian artillery or air-defense systems and then relay the coordinates to the loitering munition operators for a precision strike.

These operational challenges were compounded by severe industrial problems, a fact acknowledged even by the Russian government. As one report noted:

“A recent admission by the MOD is that most of the drones produced in Russia currently do not meet MOD’s tactical and technical requirements.”

At the heart of this failure was Russia’s weak “element base”—its domestic capacity for producing high-quality microelectronics, sensors, and other key components. This forced a heavy reliance on non-Russian parts, making the industry vulnerable to sanctions. Furthermore, a fragmented approach among various Russian developers hindered cooperation and stifled innovation, preventing the creation of a robust, self-sustaining drone manufacturing ecosystem. These glaring industrial and capability gaps created a vacuum on the battlefield, one that was about to be filled by an entirely different class of technology.

4.0 The Revolution from Below: Commercial Drones Take the Battlefield

The strategic vacuum created by the shortcomings of Russia’s military-industrial complex was filled not by a new state-led program, but by a spontaneous, bottom-up movement. The widespread adoption of cheap, commercially available drones—a trend dubbed the “Mavic phenomenon”—marked a true “revolution from below.” This grassroots adaptation stood in stark contrast to the rigid, top-down procurement pipelines of the formal military, demonstrating how simple, accessible technology could meet urgent battlefield needs when traditional systems failed.

Commercial drones became indispensable for a simple reason: they were cheap, easy to use, and available in the vast quantities required for a war of attrition. While military-grade ISR drones are expensive and scarce, first-person view (FPV) drones adapted for military use can cost as little as $300 and can be flown effectively after just a week of training. These drones provided Russian units with a desperately needed tactical ISR capability, allowing them to see over the next hill, spot for artillery, and conduct reconnaissance in urban environments.

This influx of technology was not driven by the MOD but by a network of Russian volunteer groups and influential pro-Russian military bloggers on Telegram. These groups raised funds, purchased commercial drones and parts, and delivered them directly to units on the front lines. The strategic implication of this was profound: a parallel, citizen-driven supply chain emerged to bypass the state’s rigid and failing military-industrial complex. Their influence became so significant that when the Russian Customs office held up drone imports, these bloggers publicly accused the government of obstruction, forcing an official response.

Common Commercial Drones and Their Military Adaptation

| Drone Model/Type | Observed Use/Significance |

| DJI Models (Mavic, Matrice, Phantom) | The most common commercial drones used for tactical ISR, artillery spotting, and battle damage assessment. Their ease of use and availability make them the workhorses of the front line. |

| Autel Robotics Models | Used alongside DJI drones for similar short-range reconnaissance and surveillance missions, filling critical gaps in battlefield awareness. |

| First-Person View (FPV) Drones | Originally designed for racing, these highly agile drones have been weaponized by rigging them with explosives, turning them into cheap, makeshift loitering munitions for precision strikes on troops, vehicles, and fortifications. |

The mass adoption of these civilian systems was not without challenges. It required the rapid, on-the-fly development of entirely new tactics and operational procedures to maximize their effectiveness while minimizing their vulnerabilities, ushering in a new chapter in tactical warfare.

5.0 New Rules for a New War: The Evolution of Drone Tactics

The proliferation of commercial drones on the battlefield was so rapid and widespread that it forced soldiers on both sides to invent new tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) in real time. This tactical evolution was not handed down from general staff but emerged organically from the front lines, fundamentally transforming how small units operate. The battlefield became a live-fire laboratory where survival and success depended on the ability to learn and adapt faster than the enemy.

This learning process was often brutal, with high equipment loss rates due to operator inexperience.

“Some asserted that every third quadcopter sent to the Russian force since March 2022 was lost during the first or second mission because of a lack of operator skill.”

In response, Russian volunteer groups organized events like the “Dronnitsa” meeting in September 2022. This “train-the-trainers” conference brought together hundreds of civilian and military operators to standardize training, share lessons learned, and establish an instructor corps to disseminate best practices. Through Telegram channels, these groups circulated crucial operational security protocols to help operators survive. These protocols emphasized minimizing the electronic and physical signature of operators, mandating tactics such as using separate launch and recovery sites, avoiding repeated use of the same locations, and disabling all personal electronics to avoid detection and counter-battery fire.

In offensive operations, drones became indispensable. A small quadcopter could be used to “look over a hill” or scan the next street for ambushes during urban combat. In some cases, three drones would accompany an assault group: one to monitor for enemy artillery, a second to scan for fortifications, and a third to provide overwatch for the advancing troops. The Wagner Group, in particular, made real-time drone reconnaissance a “key element” of its close-quarters combat tactics.

As drone use became an integral part of ground operations, so too did the effort to counter them. This tactical evolution quickly bled into a technological one, sparking an invisible war of signals where control of the electromagnetic spectrum became as critical as control of the ground.

6.0 The Unseen Battlefield: Electronic Warfare and the Drone-vs-Drone Fight

The saturation of the battlefield with drones gave rise to an equally intense, though largely invisible, conflict in the electromagnetic spectrum. Electronic Warfare (EW) became a critical component of daily operations—a constant cat-and-mouse game where jamming, spoofing, and signal interception determined the life or death of a drone and its operator. Controlling this unseen battlefield became as important as controlling physical territory.

Commercial quadcopters, with their reliance on unencrypted radio and GPS signals, are highly vulnerable to EW. A successful electronic attack can cause a drone to lose contact with its operator, forcing it to fall from the sky, veer off course, or automatically return to its launch point, exposing the operator’s location. Both sides have systematically employed GPS jamming and communications disruption to create “no-fly zones” for enemy drones and to protect their own forces.

This has led to a rapid cycle of countermeasures and technological adaptations. Russian forces have demonstrated frequency-hopping agility, creating brief operational windows to fly their UAVs when facing successful Ukrainian jamming. Other key developments include:

- Drone Detection: Systems like DJI’s Aeroscope are used to detect commercial drones, identify their flight path, and pinpoint the operator’s location, making them a high-priority target for artillery.

- “Reflashing” Drones: To counter detection and jamming, Russian operators began “reflashing” their commercial drones—modifying the firmware to change operating frequencies and remove manufacturer-imposed flight restrictions.

- Hardened Communications: Recognizing the vulnerability of radio links, Russian engineers have developed fiber-optic guided FPV drones. These “wired” drones are immune to jamming, providing a stable, high-quality video feed and concealing the operator’s location from radio direction-finders.

This technological arms race has also highlighted a starkly asymmetric cost exchange in counter-UAV (C-UAV) operations. To shoot down a medium-sized Russian military drone like the Orlan-10, Ukrainian forces often must expend a far more expensive Man-Portable Air-Defense System (MANPADS), creating an unsustainable cost ratio. For smaller commercial drones, the fight is less about missiles and more about the relentless EW struggle for control of the airwaves.

When Russia’s domestic drone production and tactical adaptations proved insufficient to meet the war’s demands, Moscow was forced to look abroad for more powerful and reliable systems, turning to a new strategic partner.

7.0 Foreign Reinforcements: Russia’s Iranian Drone Campaign

Facing significant shortages in its own long-range strike capabilities, Russia made a strategic decision to acquire uncrewed systems from Iran. This partnership was the culmination of the industrial failures detailed previously, serving as a stark admission of the Russian military-industrial complex’s inability to meet the demands of modern, attritional warfare. This dependency forced a major military power to rely on a sanctioned state for critical strike capabilities, and it became a cornerstone of Russia’s campaign to cripple Ukrainian critical infrastructure.

The primary systems acquired were the Shahed-136 and Shahed-131 loitering munitions, which Russia renamed the Geran-2 and Geran-1, respectively. These “one-way attack” drones offered capabilities that Russia’s own arsenal largely lacked: a long operational range, a significant warhead, and resilience to some forms of electronic jamming.

Their strategic purpose was to support Russia’s doctrine of a “strategic operation for the destruction of critically important targets” (SODCIT). This campaign aimed to achieve several objectives simultaneously: weaken Ukraine’s defense-industrial capacity, undermine the Ukrainian population’s will to fight by targeting energy and utility infrastructure, and make Ukraine a greater economic burden on its Western partners, thereby eroding their resolve.

With ranges in the hundreds of kilometers, the Iranian drones proved effective at striking both military targets and critical infrastructure deep inside Ukraine. To secure a long-term supply, Russia and Iran agreed to a plan to construct a factory in Yelabuga, Russia, with the goal of domestically producing at least 6,000 Iranian-designed drones. This move signaled a deepening military-industrial partnership, designed to provide Russia with a sustainable arsenal of long-range loitering munitions for a protracted conflict.

The lessons from Ukraine’s drone war did not remain confined to the region. The conflict has acted as a powerful accelerant for global military trends, with profound consequences for international security.

8.0 The Global Ripple Effect: The Democratization of Air Power

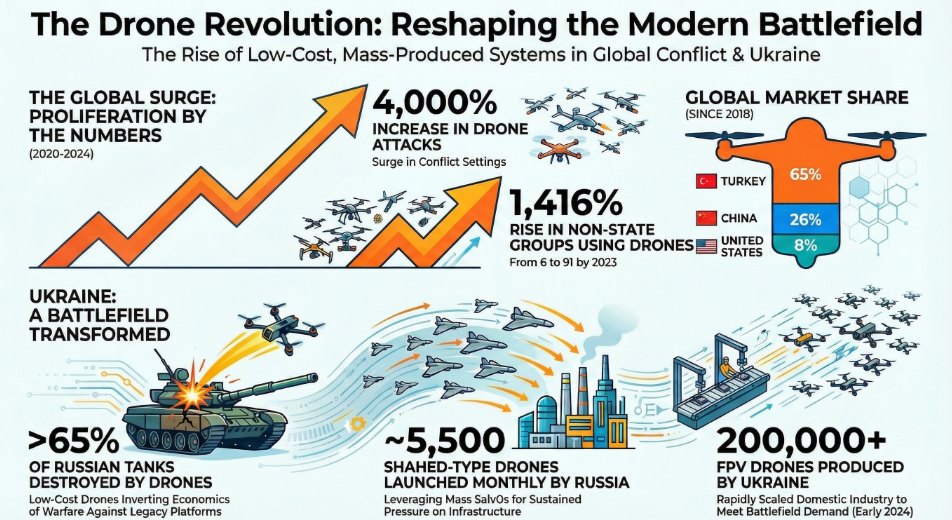

The war in Ukraine has dramatically accelerated the global proliferation of military and weaponized commercial drones, fundamentally reshaping the international arms market and making potent aerial capabilities accessible to a wider range of actors than ever before. This “democratization of air power” signifies a paradigm shift where advanced aerial surveillance and precision strike are no longer the exclusive domain of major military powers.

The era of Israeli and American domination of the drone market is over. New suppliers, including China, Turkey, and Iran, have emerged as major exporters of low-cost yet effective military drones. In 2022, Turkey overtook China as the world’s largest supplier, driven by the battlefield successes of its Bayraktar TB2. This new market provides states and non-state groups with unprecedented access to systems that can level the playing field against technologically superior adversaries.

This proliferation is occurring at an astonishing rate. According to an analysis by Vision of Humanity, between 2018 and 2023:

- The number of states using drones increased from 16 to 40.

- The number of non-state armed groups using them skyrocketed from 6 to 91—an increase of over 1,400 percent.

This rapid spread of technology makes conflicts more complex and accountability for civilian harm more difficult.

“The sheer number of drone attacks makes it harder to track, investigate, and hold perpetrators accountable for civilian harm.”

The widespread use of drones is also forcing a re-evaluation of military force structure. The traditional categories of “expendable” assets (like ammunition) and “survivable” assets (like fighter jets) are now complemented by new classifications: “attritable” assets, which are low-cost systems whose loss poses no strategic consequences, and “risk-tolerant” assets, which are medium-tier uncrewed systems that commanders can afford to lose if militarily necessary. This new taxonomy gives commanders greater flexibility, allowing them to tailor their risk exposure to a given mission. However, this rapid, largely unregulated proliferation is also raising profound legal, ethical, and strategic questions that the international community is only beginning to grapple with.

9.0 Conclusion: A New Era of Warfare

The war in Ukraine has served as a crucible for drone warfare, forging a new reality where organizational agility has proven just as crucial as industrial rigidity. The conflict has accelerated a fundamental shift in the character of modern combat, demonstrating that the ability to rapidly adapt and integrate new technologies is a decisive factor on the 21st-century battlefield. The “revolution from below”—driven by the necessity of adapting cheap commercial technology—was a direct indictment of Russia’s pre-war planning and production model.

This conflict has codified several key transformations. It has confirmed the “democratization of air power,” where cheap, accessible drones provide capabilities once reserved for advanced air forces. It has placed Electronic Warfare at the center of tactical operations, turning the electromagnetic spectrum into a critical warfighting domain. It has rewritten the economics of attritable warfare, where low-cost systems can effectively neutralize high-value assets. Finally, it has saturated the modern battlefield with a persistent layer of sensors, making concealment and surprise increasingly difficult to achieve.

The primary lesson from Ukraine is that drones are not a simple replacement for conventional forces but a powerful and essential complement that extends human capacity. Success in future conflicts will not belong to the side with the most expensive platforms, but to the one that can build a military-industrial ecosystem capable of rapid innovation and adaptation. As this evolution continues, the push toward greater autonomy, AI-augmented systems, and drone swarms is already underway. This new era of warfare demands not only new technologies but also new doctrines, ethical frameworks, and international norms to manage a world where the sky is open to all.

10.0 References

- Astrakhan, Dmitry. “Drone Amidst the Clear Sky: How Drones Change the Course of the Special Military Operation” [Дрон среди ясного неба: как беспилотники меняют ход СВО]. Iz.ru, October 24, 2022. https://iz.ru/1414691/dmitrii-astrakhan/dron-sredi-iasnogo-neba-kak-bespilotniki-meniaiut-khod-svo.

- Byrne, James, Gary Somerville, Joe Byrne, Jack Watling, Nick Reynolds, and Jane Baker. Silicon Lifeline. RUSI, August 2022. https://static.rusi.org/RUSI-Silicon-Lifeline-final-web.pdf.

- Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. Telegram post. December 13, 2022. https://t.me/bmpd_cast/14023.

- DeYoung, Karen, and Joby Warrick. “Russia-Iran Military Partnership ‘Unprecedented’ and Growing, Officials Say.” Washington Post, December 9, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/12/09/russia-iran-drone-missile/.

- Game of Drones. Telegram post. December 22, 2022. https://t.me/droneswar/5218.

- Gerasimenko, Olesya. “They Just Drove in a Column, Like They Were Going to a Parade. How an Employee of Navalny’s Headquarters Got into the War and Refused to Continue It” [Просто колонной ехали, как на парад. Как сотрудник штаба Навального попал на войну и отказался ее продолжать]. BBC.com, May 12, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-61415343.

- Grau, Lester W., and Charles K. Bartles. The Russian Reconnaissance Fire Complex Comes of Age. University of Oxford, Changing Character of War Center, May 2018. https://www.ccw.ox.ac.uk/blog/2018/5/30/the-russian-reconnaissance-fire-complex-comes-of-age.

- Kofman, Michael, Katya Migacheva, Brian Nichiporuk, Andrew Radin, Olesya Tkcheva, and Jenny Oberholtzer. Lessons from Russia’s Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. RAND Corporation, 2017.

- Kofman, Michael, Anya Fink, Dmitry Gorenburg, Mary Chesnut, Jeffrey Edmonds, and Julian Waller. Russian Military Strategy: Core Tenets and Operational Concepts. CNA, August 2021. https://www.cna.org/reports/2021/08/russian-military-strategy-core-tenets-and-operational-concepts.

- Linyov, Vladimir. “Striking from Above” [Удар с высоты]. Krasnaia zvezda, No. 77, July 18, 2022. https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/78826190.

- Nazarenko, Alexander, Eduard Shakirzyanov, and Alexander Chogovadze. “UAV in reconnaissance and fire contours” [БпЛА в разведывательно-огневых контурах]. Arsenal Otechestva magazine, 5 (55), 2021.

- Oryx. “Attack of the Drones: Listing Russian Loitering Munitions Used in Ukraine.” Oryxspioenkop.com, April 13, 2022. https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2022/04/attack-of-drones-listing-russian.html.

- Oryx. “Nascent Capabilities: Russian Armed Drones over Ukraine.” Oryxspioenkop.com, April 7, 2022. https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2022/04/nascent-capabilities-russian-armed.html.

- Slusher, Matthew N. “Lessons from the Ukraine Conflict: Modern Warfare in the Age of Autonomy, Information, and Resilience.” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), December 2025.

- Spink, Lauren. “Drones are Changing How Wars Harm Civilians.” Just Security, November 4, 2025.

- Stephens, Rhordan. “How drones have shaped the nature of conflict.” Vision of Humanity, June 13, 2024.

- “The Russian Ministry of Defense said that most domestic UAVs do not meet its requirements” [В Минобороны РФ заявили, что большинство отечественных БПЛА не отвечают его требованиям]. Tass.ru, September 27, 2022. https://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/15885129.

- Wackwitz, Kay. “The Role of FPV Drones in the Military Market.” Drone Industry Insights, November 20, 2024.

- Watling, Jack, and Nick Reynolds. Ukraine at War: Paving the Road from Survival to Victory. RUSI, July 2022.