5 Surprising Truths About Assisted Dying

Introduction: A Data-Driven Look at a Divisive Topic

Assisted dying is one of the most emotionally charged and polarizing topics of our time, often dominating headlines and fueling passionate debate. The conversation frequently revolves around deeply personal beliefs, ethical principles, and profound fears about life, death, and vulnerability. While these discussions are vital, they can also obscure the facts on the ground.

This article moves beyond the heated rhetoric to examine what legislative records, global experiences, and peer-reviewed data actually tell us about the practice of assisted dying. The reality is often more nuanced and complex than the public debate suggests. By looking closely at the evidence from jurisdictions where assisted dying is legal, we can uncover several counter-intuitive truths that challenge common assumptions and foster a more informed conversation.

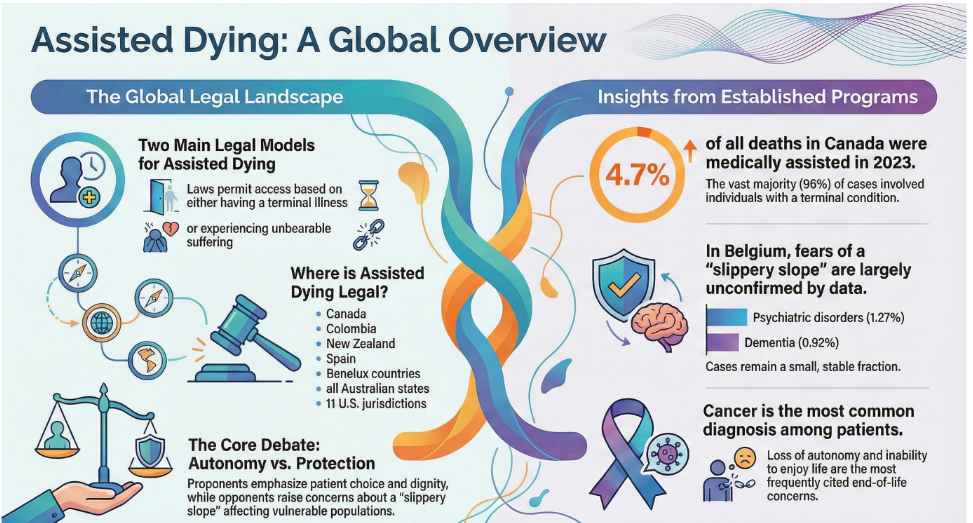

1. The “Slippery Slope” Is More Complicated Than You Think

A central argument against legalizing assisted dying is the fear of a “slippery slope”—the idea that permitting it for terminally ill individuals will inevitably lead to a broad expansion for other conditions, including non-terminal psychiatric disorders. Opponents worry that safeguards will erode, and eligibility will creep ever wider.

However, data from a comprehensive health registry study in Belgium, which has permitted euthanasia since 2002, presents a more complex picture. The analysis, covering over two decades (2002-2023), found that euthanasia for psychiatric disorders has not increased at a faster rate than euthanasia for other reasons, such as terminal cancer. Instead, it has followed similar overall trends. In contrast, cases involving dementia have increased at a faster rate than other types.

To contextualize these trends, it is crucial to look at the scale. Over the entire 21-year period studied, which included a total of 33,592 cases, euthanasia for psychiatric disorders and dementia represented extremely small portions of the total, at 1.27% and 0.92% respectively. The data suggests the “slippery slope” is not a uniform, inevitable slide. Instead, the trends differ significantly by condition, demanding a more nuanced conversation about specific safeguards rather than a blanket argument against the principle itself.

2. For Most, the Choice Is About Dignity, Not Just Pain

A common assumption is that people seek an assisted death primarily to escape unbearable physical pain. While managing pain is a critical component of end-of-life care, official data shows that the primary motivations for requesting assisted dying are often rooted in concerns about autonomy and quality of life.

Data from multiple jurisdictions reveals that the loss of independence and the inability to engage in meaningful activities are the most frequently cited reasons. A study on requests for medical assistance in dying and official state reports consistently places existential concerns ahead of physical suffering. For example, Oregon’s official 2015 Death with Dignity Act report details the primary end-of-life concerns of those who use the law.

“The three most frequently mentioned end-of-life concerns were loss of autonomy (89.5%), decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (89.5%), and loss of dignity (65.4%).”

This distinction is profoundly important. It shows that the desire for an assisted death is often not just a reaction to physical symptoms, but a considered response to a person’s deteriorating sense of self, their independence, and their personal definition of what makes a life worth living.

3. Rising Numbers Aren’t the Whole Story—Demographics Are a Key Factor

News reports often highlight the rising number of assisted deaths year-over-year in countries where it is legal. These figures, presented without context, can be alarming and may be misinterpreted as evidence of a runaway expansion of the practice. While the number of cases is indeed growing, this is not the whole story.

Belgian studies analyzing trends over the last decade reveal the statistical nuance. While the raw number of cases grew at a rate of 7% per year (a rate ratio of 1.07), that number falls to 5% per year (a prevalence rate of 1.05) when adjusted for demographic shifts like population aging. This difference confirms that a substantial portion of the increase is attributable to a larger, older population with a higher prevalence of terminal illness, not solely to a change in practice or attitudes.

Understanding this demographic context is crucial. While the practice is certainly becoming more established and accepted where it is legal, attributing the entire increase to a cultural shift or weakening safeguards is a misreading of the data. Population dynamics are a powerful, and often overlooked, driver of the statistics.

4. The Medical Community Is Moving from “No” to “Neutral”

The medical profession has traditionally been opposed to assisted dying, a stance often rooted in the Hippocratic Oath’s core principle to “do no harm.” However, in recent years, the position of the global medical community has become far more complex and is showing a clear shift away from outright opposition.

Major professional bodies, including the British Medical Association, the UK’s Royal College of Nursing, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the California Medical Association, have moved from positions of opposition to neutrality. This change does not signify universal approval but reflects a growing recognition that their members hold a diverse range of conscientious beliefs. It also signals a desire to engage constructively in the public and legislative debate rather than simply opposing any change to the law.

Of course, the medical community is not monolithic, and significant concerns remain. A US survey of physicians revealed that 60% doubt that non-psychiatrists are sufficiently trained to screen for depression in patients requesting an assisted death. This underscores the professional anxieties about implementing safeguards effectively. Nonetheless, the broader shift to neutrality is a significant development, indicating that the medical world is grappling with the complexities of the issue in a more open and publicly engaged way.

5. Turning Principle into Law Is a Painstakingly Detailed Process

Legalizing assisted dying is far from a simple yes-or-no vote. The process of turning ethical principles into workable law is a monumental task of legal and procedural engineering, subject to immense scrutiny.

A procedural analysis by the UK’s Hansard Society of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill serves as a powerful case study. The legislative process involved a level of detail that is almost unprecedented for a private member’s bill. The Public Bill Committee, tasked with clause-by-clause examination, held 29 separate sittings and generated an 852-page compilation of its debates. At one point, legislators had already tabled 942 amendments for consideration for the first day of the bill’s later debate stage alone.

This intense process forces legislators to meticulously define and debate every critical component of the law. This includes establishing precise eligibility criteria, defining “terminal illness,” designing robust mental capacity assessments, detailing procedures for medical consultation, and creating conscience protections for medical staff who do not wish to participate. This exhaustive scrutiny is not procedural obstruction; it is the fundamental process of building powerful safeguards directly into the legal framework, transforming a contentious principle into meticulously engineered public policy.

Conclusion: A More Informed Conversation

The data reveals a reality of assisted dying that is more measured, procedurally rigorous, and demographically influenced than the polarized public debate suggests. Common fears about a “slippery slope” are not uniformly supported by the data, the primary motivations are more existential than physical, and the legislative path is one of painstaking detail.

As more societies grapple with this profound issue, perhaps the most important question is not simply if we should permit assisted dying, but how we can ensure our laws are built with compassion, precision, and an unwavering commitment to protecting the vulnerable.

References

- “(PDF) Trends in assisted dying among patients with psychiatric disorders and dementia in Belgium: A health registry study – ResearchGate”

- “Incidence of reported cases of euthanasia adjusted for demographic composition: a study of ten years of Belgian administrative data (2014–2023) – NIH”

- “Assisted dying – The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill: Rolling news – Hansard Society”

- “Assisted suicide – Wikipedia”

- “Reasons for requesting medical assistance in dying – PMC – NIH”